![E-Levy: Pay just GH¢1/Ey? GH¢1 p? [Article]](https://citinewsroom.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/E-levy-graphs-7.jpeg)

The Government of Ghana through the 2022 Budget Statement sought to introduce a tax on electronic transactions to help generate revenue. The tax was christened the ‘E-Levy’. The tax will cover electronic transactions such as mobile money payments, bank transfers, merchant payments, and inward remittances.

This proposed tax has been undeniably the most controversial aspect of the 2022 Budget. In this article, I will analyze the growth of electronic transactions/digital payment systems in Ghana. I will discuss some merits and demerits of the ‘E-Levy’ in its current form. Finally, I will make proposals of alternative ways in which the levy may be implemented and its implications on the government’s revenue generation capacity both in the short-term and long term.

Structure of the Payment Systems in Ghana

COVID-19 took a serious toll on health systems and economies across the world, with the attendant loss of many lives. As of the time of writing, over 5.3 million lives had been lost globally to the virus. However, the pandemic spurred the growth of ‘Fintech’ and digital payment systems across the world as people avoided the use of cash to prevent the spread of the virus.

In March 2020, the Bank of Ghana working with banks and mobile money operators (MNOs) decided to exempt mobile money transactions below Ghs 100 from charges/fees. Further, limits on mobile money transactions were increased. This was to encourage the use of mobile money during the pandemic.

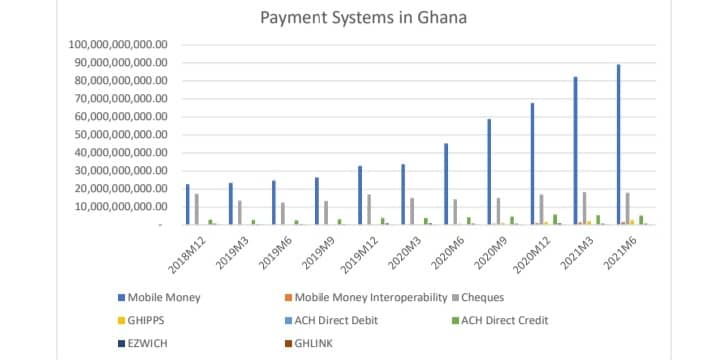

Indeed, between December 2019 and June 2021, mobile money grew at a record 52% with mobile money transactions across networks (mobile money inter-operability) growing by 141%. Cheques on the other hand grew by 19%, whilst ACH direct credit grew by 9%. Only GHIPPS grew faster than mobile money over the same period, recording a growth rate of 165%.

As Figure 1 shows, mobile money is now the most dominant payment system in Ghana. As at June 2021, it was almost 5 times larger than its closest competitor (cheques). It was also 17 times and 35 times larger than ACH direct credit and GHIPPS which came in 3rd and 4th respectively.

Figure 1: Payment Systems in Ghana

Source: Constructed by Authors based on data from the Bank of Ghana.

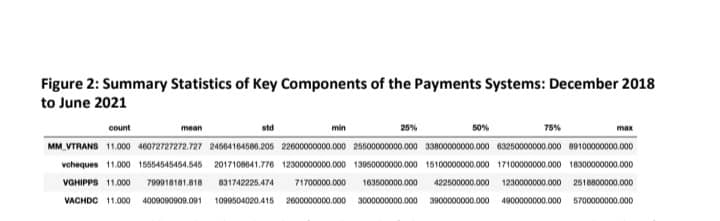

Figure 2: Summary Statistics of Key Components of the Payments Systems: December 2018 to June 2021

Source: Constructed by Authors based on data from the Bank of Ghana. MM_VTRANS represents the value of mobile money transactions, cheques represent the value of cheque transactions, VGHIPPS represents the value of GHIPPS transactions and finally, VACHDC represents the value of ACH direct credit transactions.

Figure 2 shows that the median value of mobile money transactions over the period was Ghs33.8 billion, with a minimum value of Ghs 22.6 billion and a maximum value of Ghs 89.1 billion. The mean value of mobile money transactions of Ghs 46 billion, far exceeds the median of Ghs 33.8 billion confirming the growth (that is a right skew) in mobile money transactions over time.

Cheques recorded a median value of Ghs 15.1 billion, with a minimum value of Ghs12.3 billion and a maximum value of Ghs 18.3 billion. The mean value of cheque payments was Ghs 15.5 billion, very similar to its median value. ACH direct credit recorded a median value of Ghs 3.9 billion, with a minimum value of Ghs 2.6 billion and a maximum value of Ghs5.7 billion.

The mean value of ACH direct credit was Ghs 4 billion, very similar to its median value. Finally, the median value of GHIPPS transactions was Ghs 422.5 million, with a minimum value of Ghs 71.7 million and a maximum value of Ghs 2.518 billion.

The mean value of GHIPPS transactions of Ghs 799.9 million far exceeds its median value of Ghs 422.5 million thus suggesting growth (right skew) in GHIPPS transactions. It is thus obvious that mobile money dominates the payments system, that is why most of the discussions of the E-Levy have focused on mobile money.

Given the growth in mobile money and its size, it appears the government believes that the industry is mature enough to be taxed. However, I believe that the industry is still growing and has much more room for growth. A tax that is not well designed, may have adverse effects and may have the potential of slowing down or reversing the gains made so far in terms of mobile money and more generally digital payments systems.

- The growth in mobile money has been due to its broader use beyond purchasing airtime. It is used by individuals to pay bills, to pay merchants, and to send money to family and friends amongst others. Businesses have also adopted mobile money in receiving payments from their clients, making business-to-business payments, and even paying the salaries of their employees.

Despite the convenience of using mobile money, the danger of the E-Levy in its current form is that individuals and businesses may resort to alternative means of payments where they do not incur a tax. This kind of behaviour is referred to as the Laffer effect. This effect suggests that the imposition of taxes beyond the optimal level may lead to a fall in revenue generation due to a change in behaviour by economic agents.

That is, are mobile money payments ‘elastic’ or something that economic agents can do away with? The critical assumption by policymakers is that mobile money is inelastic or that the taxes are unlikely to significantly affect the use of mobile money services. If this assumption turns out to be false, then the government may not raise as much revenue as it anticipates.

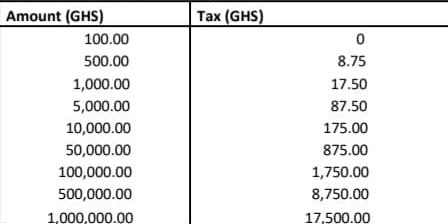

As an illustration as to the mechanisms at play, if a business made a payment worth Ghs 100,000 to a supplier, it would incur a tax of Ghs 1,750 (see Table 1). If it could avoid this tax by making payments by other means, it may have a high incentive to do so. Again, assume that Mr. Adom has to pay his mason Ghs 10,000 for works that the mason has done on the house that Mr. Adom is building. Mr. Adom would have to pay a tax of Ghs 175 (see Table 1). Mr. Adom may seek to avoid the tax by paying the mason with cash.

Thus, the tax creates a distortionary effect in the market and incentivizes economic agents to use other means of payment such as cash that are not as efficient as mobile money. This is therefore likely to harm the digitization agenda, reduce financial inclusion, create distortions and rigidities in the payments system, reduce innovations in the digital payments systems and ultimately reduce economic growth and development.

Table 1: Transactions and E-Levy Tax

Source: Constructed by Authors.

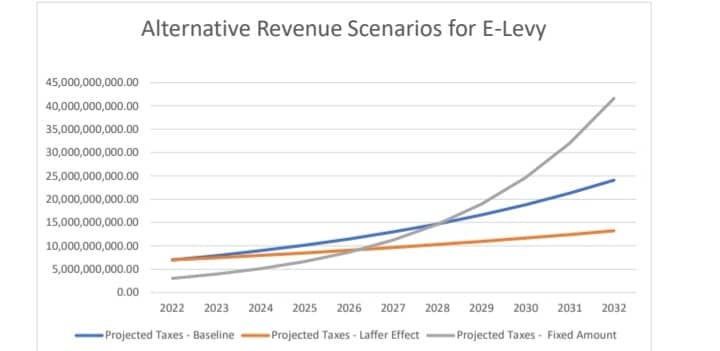

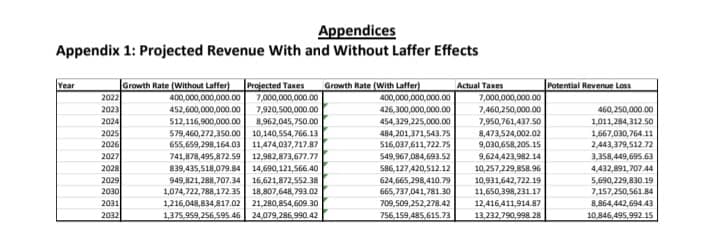

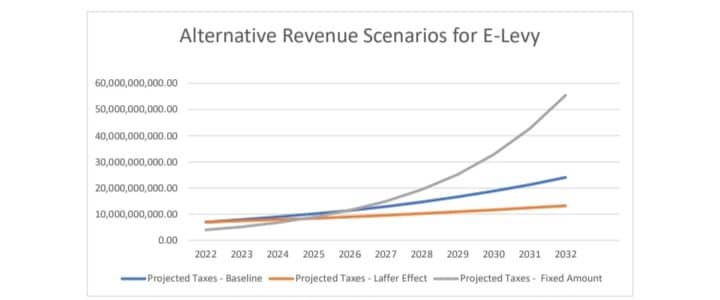

I now focus my attention on analyzing the effects of the proposed E-Levy on revenue generation both in the short-term and long-term. I also analyze the impact of my alternative proposal of a fixed amount and its effects on revenue generation in the short-term as well as long-term. I present this in Figure 3. Figure 3 shows the taxes that the government projects to receive from the E-Levy between 2022 and 2025. When I gross up the E-Levy to 100%, it suggests that the Government expects about Ghs 400 billion from digital transactions in 2022. Mobile money alone I estimate will be about 120 billion, constituting about 30% of all digital transactions in terms of value. The figures from 2022 to 2025 were simulated to resemble the projections by the government. The figures from 2026 to 2032 are based on my own estimates assuming the trends from 2022 to 2025 continue – that is assuming a cumulative annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.15% per annum.

The government projects an amount for the E-Levy of GHS 10.87 billion in 2024. Given the projection of Ghs 6.96 billion in 2022, this suggests a cumulative annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.15%. I use this rate through to 2032 in my baseline projections.

The Blue line in Figure 3 shows the growth in tax revenues from the E-Levy in its current form assuming no Laffer effects (baseline projects). In the absence of the E-Levy, this growth scenario is plausible. However, given that the E-Levy in its current form (baseline scenario) may create distortionary effects, I assume that mobile money transactions will grow by half of 13.15% (about 6.575%). This leads to the tax revenues projections that I call Laffer Effect Tax Revenues (orange line). Of course, various other growth rates can be simulated to

understand how various growth rates will affect revenue projections.

More generally, as can be seen from the graphs, a reduction in the growth rate of mobile money transactions due to potential changes in behaviour will lead to lower revenues than the government has projected both in the short-term and long-term. For example, my projections show that if mobile money grows at 6.575% instead of 13.15% due to the Laffer effects, the government will generate tax revenues from the E-Levy of only Ghs 8.5 billion instead of the estimate of about Ghs 10 billion in 2025. This represents a revenue deficit of Ghs 1.67 billion (see Appendix 1). This deficit grows to Ghs 10.8 billion by 2032.

Figure 3: Alternative Revenue Scenarios for the E-Levy

Source: Constructed by Authors based on simulations and data from the 2022 Budget Statement.

Given the potential distortionary effects of the E-Levy, I propose a fixed amount for the E- Levy. This fixed amount can be designed in various forms.

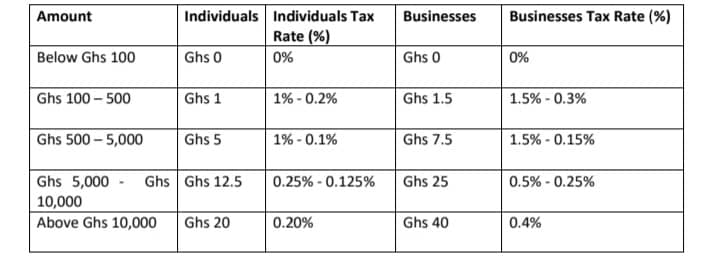

Table 2 shows an example of how such a tax can be designed. The Table shows that individuals and businesses may be taxed differently given that they have different sensitivities to tax. For individuals, an example could be Ghs 1 for amounts between Ghs 100 – 500, Ghs 5 for transactions between Ghs 500 and Ghs 5,000, Ghs 12.5 for transactions between Ghs 5,000 and Ghs 10,000 and Ghs 20 for transactions above Ghs 10,000.

The amounts for business-level transactions are slightly higher. Amounts below Ghs 100 would not attract any taxes as has been proposed by the government. A design such as the one shown in Table 2, however, may be complex to administer and communicate. However, over time people are likely to become familiar with it. Another disadvantage is that though the amounts appear to be progressive, it technically isn’t when we look at the percentage tax rates both for individuals and businesses.

This is very obvious from Table 2. However, compared to the current E-Levy, this proposal has some strengths. Across the board, the highest tax rate for individuals is 1% whilst the highest tax rate for businesses is 1.5%. My design also accounts for the different sensitivities of individuals and businesses to taxes. Further, my design has an advantage over the current E-Levy for larger transactions because of the lower percentage tax paid. The current E-Levy has high disincentives for large transactions because of the cedi tax that has to be paid.

Consequently, my design is softer on low-income earners and does not provide a significant disincentive for high-value transactions. My proposal is similar to the transaction fees that MTN for example charges for its mobile money services – 1% of the value of transactions capped at Ghs 10. However, it is also different from the MTN example in various respects.

Table 2: An Example of a Fixed Amount Tax Design

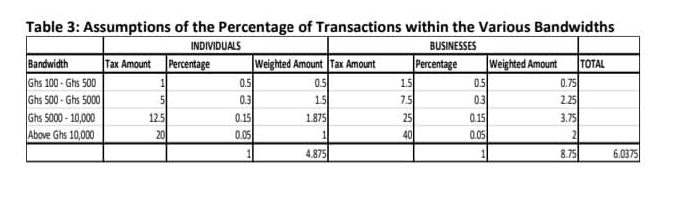

I made some assumptions as to the percentage of transactions that would fall within the various bandwidths to help with the revenue projections under this regime. I assumed that 50% of transactions would fall within Ghs 100 to Ghs 500, 30% of transactions will fall within Ghs 500 to Ghs 5000, 15% of transactions will fall within Ghs 5000 to Ghs 10000 and finally, 5% of transactions will be above Ghs 10,000.

The same assumptions were made for both individual and business level transactions for simplicity. I believe that these assumptions are reasonable. Anecdotal evidence suggests that most mobile money transactions for example are small size transactions below Ghs 500. Consequently, my proposal is likely to gain acceptance by the majority of Ghanaians. Indeed, it can be marketed as E-Levy: Pay Just Ghs 1/ EyGhs 1 P. Of course, the catch is that Ghs 1 is for transactions below Ghs 500. My assumptions can easily be modified by policymakers who may have better data to observe the implication of the various percentages for revenue generation purposes.

Table 3: Assumptions of the Percentage of Transactions within the Various Bandwidths

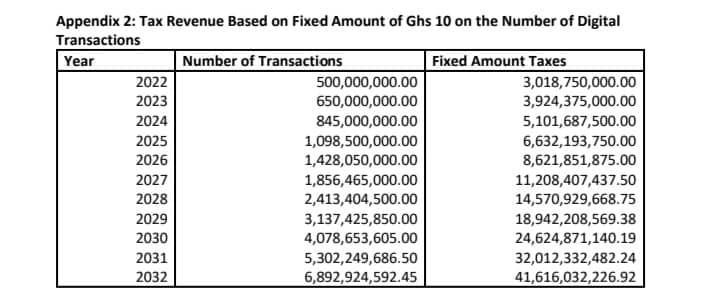

Further, for my revenue generation exercise, I assumed that the total number of mobile money transactions will grow to about 400 million by the end of 2022 (see Appendix 2). For context, the number of mobile money transactions as of June 2021 was 338 million. Given that mobile money transactions dominate the payments system, I assume that mobile money transactions represent 80% of the number of all digital transactions.

Thus, I estimate the total number of digital transactions to be 500 million by 2022. I believe that this is a reasonable and conservative assumption. Based on data that I obtained from the Bank of Ghana, mobile money constituted about 95% of the number of the following transactions; mobile money, mobile money interoperability, cheques, GHIPPS, ACH direct credit, ACH direct debit, EZWICH, and GH Link. Notably, the data does not include the number of remittances. I further assumed that the number of digital transactions will grow by 30% per annum over the period.

This is due to the lower distortionary effects of charging a fixed amount. As can be seen from Table 3, the average fixed amount for both individuals and businesses is Ghs 6.0375. This was based on the assumption that the average number of transactions will be 70% and 30% for individuals and businesses respectively.

Based on my proposal, the total tax revenue generated by the government in 2022 works out to be 3 billion (see Appendix 2);

500,000,000 ? 6.0375 = 3.018 billion

For 2025, this works out to be 6.632 billion (see Appendix 2);

1,098,500,000 ? 6.0375 = 6.632 billion

This compares to the government’s estimate of Ghs 10 billion from the baseline projections for 2025. Consequently, the fixed amount is likely to generate lower tax revenues for the government in the short term. However, it generates more revenues in the medium and long- term given that it has less distortionary effects.

My projections show that by 2026, the tax revenues from the fixed amount (Ash line) will exceed the taxes that are likely to be generated from the E-Levy in the presence of Laffer effects (see Figure 3). By 2028, the tax revenues from the fixed amount will exceed the tax revenues from the E-Levy without the Laffer effects.

By 2032, the revenue from the fixed amount will be almost twice the revenue from the baseline projections and more than three times the revenue in the presence of Laffer effects. Thus, the fixed amount is beneficial in the medium to long-term given that it has less distortionary effects. Indeed, if the mobile money transactions form a lower percentage of the number of total digital transactions (60% of total digital transactions), these effects are larger and are achieved more quickly (see Appendix 3).

The main disadvantage of a fixed amount as I have proposed, however, is that the revenues generated will be lower in the short- term. Thus, this may make my proposal undesirable to the government if it is focused on the short-term or completing its mandate which ends in January 2025.

Indeed, our previous articles (Budget 2022 and Ghana’s Public Debt) show that it would be difficult to achieve debt sustainability (70% of GDP) by 2025 without the implementation of the E-Levy in its current form. In this context, and given that my analysis shows that there will still be a revenue gap in the short term if the government implements a fixed amount for the E-Levy, what options are available to the government? One option would be for the government to consider increasing corporate taxes slightly across the board for a few years – say up to 2025.

This may be an unpalatable option as it would add to the high cost of doing business and may lead to a reduction in employment creation and corporate investments. Another alternative could be for the government to seek to be efficient in its expenditure by for example pursuing value for money, reducing wastage, and tackling corruption. It appears that policymakers believe that this option may not make a significant dent in the fiscal deficit. In the long-term, however, to maintain debt sustainability, implementing policies that grow the economy (GDP, which is the denominator of the Debt/GDP ratio) can lead to more sustainable debt.

The government can consider putting policies in place to make Ghana a leader in financial technology (Fintech) in the sub-region. FinTech is a growing area globally and Ghana can position herself strategically as the FinTech hub of Africa. Export of Fintech services could lead to the generation of foreign currency earnings, employment creation, and growth in the economy, making our debt more sustainable in the long term.

Written By;

Elikplimi Komla Agbloyor

Associate Professor, Department of Finance University of Ghana Business School

Chair of Research Committee, Tesah Capital

Appendices

Appendix 1: Projected Revenue With and Without Laffer Effects

Appendix 2: Tax Revenue Based on Fixed Amount of Ghs 10 on the Number of Digital

Transactions Appendix 3:Revenue Projections if the Number of Mobile Money Transactions Forms 60% of the Number of Total Digital Transactions

Source: Constructed by Authors based on simulations and data from the 2022 Budget Statement.

The post E-Levy: Pay just GH¢1/Ey? GH¢1 p? [Article] appeared first on Citinewsroom - Comprehensive News in Ghana.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS